Women's Work Powers the World

Hi and Welcome! This is the second issue of Palimpsest of Flesh. This month I'm thinking about the work that women do, and looking at the history of why it's overlooked, downplayed, and ignored. And a bit about how AI might change it.

Speaking of work: The Stronger Sex Was Named a Best Science Book of 2025 - Twice!

Both Library Journal (the publication for libraries and librarians that helps them pick books AKA the realest readers!) and the Next Big Idea Club named my book, The Stronger Sex as Best Books of 2025.

Love that the Library Journal is called "Stellar Selections" as stellar of course means "relating to a star" and.... that's me!

Onto the essay-of-the-month:

Corpus:

The living body of this issue (a thought lab for my writing; aka the essay).

"Man may work from sun to sun, But woman's work is never done".

On "Women's Work" and Why It Is So Undervalued

Quick Fact: Women's do more than half of the world's labor - 52% counting paid and unpaid. (Some estimates put it at closer to 65% but that 52% figure is conservative one from the United Nations.) Despite performing the majority of work, women receive only 10% of the world's income and own less than 1% of the world's property.

2025 was the year of earnest and (sometimes) honest discussion of women's work. I saw it everywhere I looked: From nuanced discussions of what mental labor is, and how women do more of it on Facebook, to some very funny Tiktoks getting really nitty-gritty about the mental load women face when partnered with men. It's been especially heartening to see how many MEN are making this viral content. Because men need to hear this stuff from other men.

@jimmyonrelationships Invisible Mental Load #mentalload #relationships #conflictresolution

♬ original sound - Jimmy Knowles

That's the good news.

On the flipside, there was the regressive and short-sighted op/ed video discussion, "Do Women Ruin the Workplace?" in the NYTimes (stats say the employees of the Times is 55% female FYI), which they changed pretty quickly to "Did Liberal Feminism Ruin the Workplace?" I'm not linking to it because I don't want to give them the link.

To be clear, yes, this was ragebait by the NYTimes, and to some extent they knew it was going to piss people off and get them talking (and clicking).

A journalist's aside: While the NYTimes is the paper of record to some extent, it is also often terribly late to stories because of the inherent small-c conservatism of the people who work there; boundary-pushing writers are not what the Times is known for. This also means that they have to publish ragebait sometimes so it seems to their readership that they are "asking the tough questions" and are part of the zeitgeist. Point being, I took that whole manufactured controversy none to seriously.

Still, it was a conversation about women's work! Which is one of those topics that feels oceanic in scope. Because if you grew up watching the women in your life very closely as I did, you'd be hard-pressed to differentiate between women's work and their lives. Unless they are pretty wealthy*, women are always working. Pretty much all women, all the time.

*And honestly, even pretty wealthy women I've known are still doing a ton of labor, both paid and unpaid, at home and in their communities.

Where is Women's Leisure?

The only part of womanhood where I found leisure: college. I have been financially independent since I was 22, paying rent, utilities, buying cars, etc. on my own after I got my degrees—but my BS in geology and BA in English from Syracuse University were fully covered by a combination of a scholarship from SU and my father's savings for me. A profound gift and one I'm grateful for.

Since college was originally designed for men, there's lots of downtime, and most college students (who aren't working to pay their way through of course, which many are) have time and space they can direct any which way. I played on a dorm-wide soccer team; smoked weed and listened to music/went to shows/watched movies with film students; was the subject in some art projects; hiked around Syracuse; and hung out with my friends of course.

I loved that time, and during the years that followed, as I worked full time throughout my 20s, as well as side-hustled like crazy, that I started really thinking about how I wanted my life and my work to look.

Growing up, I had done a lot of childcare, being one of my town's most popular babysitters, but I noticed that mothers were always "on" whether they worked outside the home or not. There was no break, no vacation, no personal time. From wealthy families to those living on the margins, none of the mothers' lives looked like they had their own time. All the men did. I knew I didn't want to live like any of the women I babysat for (ditto with my friends' moms), and I knew I liked having my own time. I bought a house when I was 27 and that was a huge amount of responsibility, and still more work. And apparently I was supposed to add babies and children to this? Where was the room in my life going to be for me?

This is a question women around the world are asking: When (and where?) do we get to relax already?

I didn't want a life of nonstop work outside the home and inside the home in the service of other people. It looked like a raw deal to me and in my 20s I realized I could opt out. (It took me years to realize that I didn't have to do these things—despite the Progressive community I was raised in, I was strongly pushed into the LifeScript for white American girls to get married, buy a home, and prioritize keeping that home, children, and husband. I could have a career after all of that if really wanted to.) I opted out of marriage, and motherhood. I threw the LifeScript out of the window and haven't looked back since.

Some days, I feel angry and scared about the life I was almost pushed into. It was close. I'm so proud of my 20-something self for seeing through the BS my culture had taught me. Just because we are born with a uterus doesn't mean we are all supposed to live the same way.

My choice is an uncommon one for women my age, but is one increasingly embraced by younger women.

It Starts in Girlhood

The expectation that women live their lives for the men and children in their lives is global and so woven into the fabrics of so many cultures that it seems normal. But it's not normal at all that half the population's time off is respected and the other half's is not. It's not right that women's constant work is normalized, and that women are encouraged and pushed into doing so much unpaid labor, from the time they are a sister, through being a girlfriend and wife, to motherhood, and grandmotherhood.

My friend Amanda Freeman, a sociologist at the University of Hartford, and co-author of Getting Me Cheap: How Low Wage Work Traps Women and Girls in Poverty wrote in her book, low-income girls in the US (and this happens around the world) start care work early:

"[Moms] were frequently leaving children in “self-care” and relying on teens and children, predominantly girls, to take care of even younger children. Lisa recorded a teen girl who, upon listening to other girls describe their routine family-care work, said, “It’s all true. It’s all similar. I am the oldest daughter too . . . living with my mom and my three siblings, so I had to play my father’s role, and I had to be the father. . . . And it was a big responsibility and it changed me a lot.”

This early work and expectation for poor and middle-income girls (and their mothers' example of constant work for all girls), shows girls early and often how their lives are not their own, but belong to other people.

And so you get to the reality of the video above, which was sent to me by Ananya Dash, after she heard me speak about some of the topics in my book with journalist Maryn McKenna on the Emory University Health Journalism Interview Series. This video is a clip from a much longer film, which is a fascinating look into Indian women's labor. It's all part of the Visible Women: Invisible Labor exhibit at the People's Archive of Rural India.

Talk to a group of older women anywhere in the world, and you will likely hear jokes, complaints (or complaints masked as jokes), about how women do the majority of the labor in the world. But it's true. In surveys (that vary a bit depending on region) women provide roughly 76% of all unpaid care work worldwide.

The UN states that women do 52% of the world's labor, and as the UN Women's site puts it:

If counted, unpaid work could exceed 40 per cent of GDP in some countries. Women do more than half of the world’s work, and nearly half of that goes unpaid, despite its demanding nature. Unpaid care work is the backbone of societies and economies, yet it remains invisible, uncounted, and unequally shared.

That 52% is a conservative estimate—others put the level at closer to 2/3 of the work.

This very much comports with how much more I see women working in the world. This isn't to say that men aren't working or contributing to the home or childcare—many men do, but most don't. That's just statistics.

And this work literally never ends. According to this article in The Guardian, women over 60 in 31 countries surveyed by spend twice as much time as older men on unpaid work.

Women interviewed for the project spoke of a relentless cycle of household tasks – cooking, cleaning, washing – as well as physically demanding duties such as collecting water and firewood. When they become too old to carry these items, many women simply resort to dragging them.

Researchers who examined employment patterns across developed and developing countries found the disproportionate amount of unpaid domestic and care work performed by women persists into older age regardless of geography.

I know some of you are here for the sports and athletics, as well as the feminism, so I'll connect the dots here for why I'm writing this essay about women's work: When girls and women are so busy caring for others, starting as children, that gives them much less time to pursue athletics.

That girls participate in sports at lower rates than boys is true everywhere in the world, and the reasons are consistent—except for girls wealthier households, lower-income girls, whether in Connecticut or Calcutta, are expected to do care work and help their overburdened mothers. Boys aren't and are free to play in the streets or the courts, and learn their time is their own from a very young age.

The AI of It All

Maybe AI wills save women from this drudgery? While the tech bros have consistently left thoughts of half the population completely out of their giant, brilliant brains/s so consistently for a decade that researchers have had time to document how lame, wide, and deep that studied ignorance is, #notalltechbros:

As Caroline Criado Perez writes in her latest newsletter, the chief economist of OpenAI, Aaron Chatterji actually talked about unpaid work and women last week:

“Whether it’s caring for children or doing household chores, these are things that need to get done,” Chatterji explained in an interview with the Financial Times. “But given that it’s not counted [in GDP], a lot of those benefits will never show up.” And so, Chatterji says, “we have to figure out ways to measure this more carefully.” And as with digital public goods before it, this latest effort to account for unpaid work is not being pushed out of a desire to count the economic contribution of women. Nor is it in fact being pushed in an effort to count the contribution of men, or indeed the contribution of any living breathing human being.

No, it seems as if the thing that might finally drive us to count the contribution of unpaid work to the global economy is…AI. Specifically, how much value AI is contributing to the global economy with all of its selfless unpaid care work.

I have my doubts that technology will save us from this work, as the AI guys seem to be prioritizing ruining literally anything and everything that makes being human fun, using it for art of all kinds, music (I was recently fooled by an AI "musician" on Spotify), and even porn. But never to actually save us from drudgery. What kind of world is one where women are still doing most of the boring work, while AI makes paintings and songs??? There's just nothing intelligent about it.

Only we can save ourselves from this system. By doing what the Indian women in the Insta video are doing (creating their own spaces to hang); by just not doing the housework to some mythical standard of "cleanliness"; by insisting boys do housecleaning chores too; and maybe by not marrying at all or having kids if you don't want to.

Because these ARE all choices for many of us (not all, not yet). And too often I see us making them because we are used to doing "women's work."

Anconeus* Archive

Small but mighty notes — contractions of thought, brief flashes of muscle memory.

*The Anconeus Muscle is a tiny connector between the arm’s upper humerus and lower ulna which allows elbow extension.

HEAR IT

I listen to the Slate Political Gabfest every week for highly informed, deeply intelligent takes on What's Going On. The highly informed crew of Emily Bazelon, David Plotz and John Dickerson have been chatting with each other for 20 years. They are a delight and there are plenty of zingers and deep thoughts in the engaging political discussion. But last week, Emily Bazelon, a Yale law professor and contributor to the NYTimes, said this and it deeply resonated with me:

My own version of feminism and female identity is to feel that strength is important. That doesn't mean that everyone feels strong all the time and that there aren't plenty of reasons to feel put-upon or mistreated. I don't mean to suggest that. But when I have a choice about feeling strong, or feeling put-upon, I have trained myself to pick strong because it feels better and it gets me further in my day.

And now for something completely different! I'm obsessed with this new musician I just found called Delilah Bon - her song "Dead Men Don't Rape" is incredibly loud, intense and full of rage in a way I haven't seen since the 90s and the Riot Grrrl bands like 7 Year Bitch (which of course had their own song by the same name). Unfortunately, she just cancelled her US tour due to safety fears for her crew and her fans, because that is where the US is right now.

SEE IT

@thecurioushumana Now, research by immunologists, virologists and geneticists is finally exposing why, illuminating the reasons for women’s long-known yet under-examined immune strength. It reveals the roles that hormones and sex chromosomes play in supercharging women’s immune cells to detect, fight and remember intruders, and in keeping their immune systems more youthful for longer than men’s.The historical lack of research into female bodies throughout medical science extends to immunology. To date, it has favoured a “one-size-fits-all approach skewed toward male biology”, says Caroline Duncombe at Stanford University in California, whose research explores the ways that sex-based differences influence immune response. The fact that immunology research is still underpinned by foundational knowledge based largely on studies of men is a problem for women. “Biological sex is one of the most important factors affecting health and disease across the lifespan,” she says, “because it affects environment and lifestyle, as well as genetics and hormones – all of which are important when you’re evaluating immune response.” But the male bias in research is also a problem for men. “[Women] have an immunity advantage that could have offered insights had it not been neglected for so long,” she says. Read more at New Scientist magazine in the article: "Women have supercharged immune systems and we now know why" by Starre Vartan #womenshealth #genes #estrogen #longevity

♬ original sound - TheCuriousHuman

READ IT

So happy to end the year on such a positive note with this interview feature in the prestigious The Open Notebook site, an incredible resource for science journalists or any journalist who covers health, animals, environment, etc. I so appreciated that Skyler Ware asked such smart questions about how I reported around the dearth of information about female bodies in some areas, and also about how trans and intersex bodies can help inform science for all bodies, a very overlooked subject. I cover all this and lots more in my book, The Stronger Sex: What Science Tells Us About the Power of the Female Body! Link in profile to read the whole article. but here's a preview:

Q: You spoke with several non-scientist experts, including a korfball player for a section on mixed-gender sports teams and elderly women in Okinawa, an area known for exceptional longevity, among others. How did you approach finding people to talk to?

A: [Finding non-scientist sources] was definitely one of my bigger challenges, because I don’t have as much experience doing that kind of reporting. For the korfball player, I actually went to the International Korfball Federation, headquartered in the Netherlands. I did the classic reporter thing, and I was like, “Who would be good to speak with? I’d love to go to a korfball game.” And they were really responsive and helpful.

Finding individuals [outside of organizations] was more difficult. I knew I wanted to go to Okinawa and speak with the older women there, but I knew that the language barrier was going to be an issue. I hadn’t done interviews in another language before. I found this woman, Christal [Burnette], through YouTube. She spoke Japanese, lived in Okinawa, [and] was part of the [Okinawa Research Center for Longevity Science] there. She’d just stumbled across this bar [where] there were 90-year-old women hanging out, and she spent the evening with them. She was like, “I’ll ask them if they’d be interested in talking to you.” She then set it up, so I paid her to be my translator and my fixer.

Hot Off The Presses

Here's what I've published most recently:

WIRED

Well this is kind of a Big Deal! I contributed to WIRED World 2026 this year—the magazine's yearly predictions guide.

My article, which is in the Health section (alongside pieces by science-writing icon Carl Zimmer and doctor/author Eric Topol, MD!!) focuses on Australian researcher Caroline Gargett—and her team including Shayanti Mukherjee, PhD—who discovered and pioneered the use of stem cells found in (easy-to-access and plentifully produced by half the planet's people) menstrual fluid.

A primary reason this took so long to discover was male researchers' discomfort with period blood. Lots more incredible details in the article, like how we may be able to one day soon bank our own stem cells for use when we need them for our own health care!

Thanks for the lovely illustration Ibrahim Rayintakath!

CNN

This piece, my first-ever for CNN Sports, came out of a pitch related to my book, The Stronger Sex, that didn't quite work out in another iteration many months back. So I retooled the focus to put it on the worldwide phenomenon of sports uniforms and how most of them aren't made for female athlete's bodies, and pitched it to my editor at CNN.

She liked the idea, and I had a very compelling (and infuriating-on-her-behalf) interview with Tess Howard, a ridiculously accomplished Olympian for Team Great Britain in field hockey, and a recent graduate of the London School of Economics (a Masters degree in Political Sociology, with distinction)!

This article starts out with Tess' experience and her push for changing athletic uniforms, but I also get into the very important subject of Low-Energy Availability and REDs which is basically what happens when female athletes underfuel (don't eat enough) because they are trying to meet cultural standards around what athletes are "supposed to" look like. This very real stress on female athletes leads to injury and dropping out of sports and is one of the reasons female athletes aren't competing at their highest levels since, depending on the sport, anywhere from 30-70% of athletes are fueling enough to perform strongly, or build muscle enough to do so.

When Olympian Tess Howard put on her new uniform for Great Britain’s women’s field hockey team in 2021, she felt something she hadn’t expected at the height of her athletic career: embarrassment.

The compression tank top and short, snug skort were meant to be performance wear. Instead, the top was too tight and low-cut, and both pieces were physically restricting Howard’s and her teammates’ movement and breathing.

“You put the top on, and your life is sucked out of you,” said Howard, recalling the skort actually made it more difficult to run. “Before games, we were all stretching it over the backs of chairs in the locker room, trying to make it fit differently.”

Very cool to speak to the changemakers like Olympian Tess Howard MBE OLY a field hockey champion who founded Inclusive Sportswear, trailrunner Bailey Kowalczyk of Nike, Prof Emeritus A.C. Hackney who pioneered research into REDs, and Jane Ogden at the University of Surrey's research into how uniforms affect young women athletes.

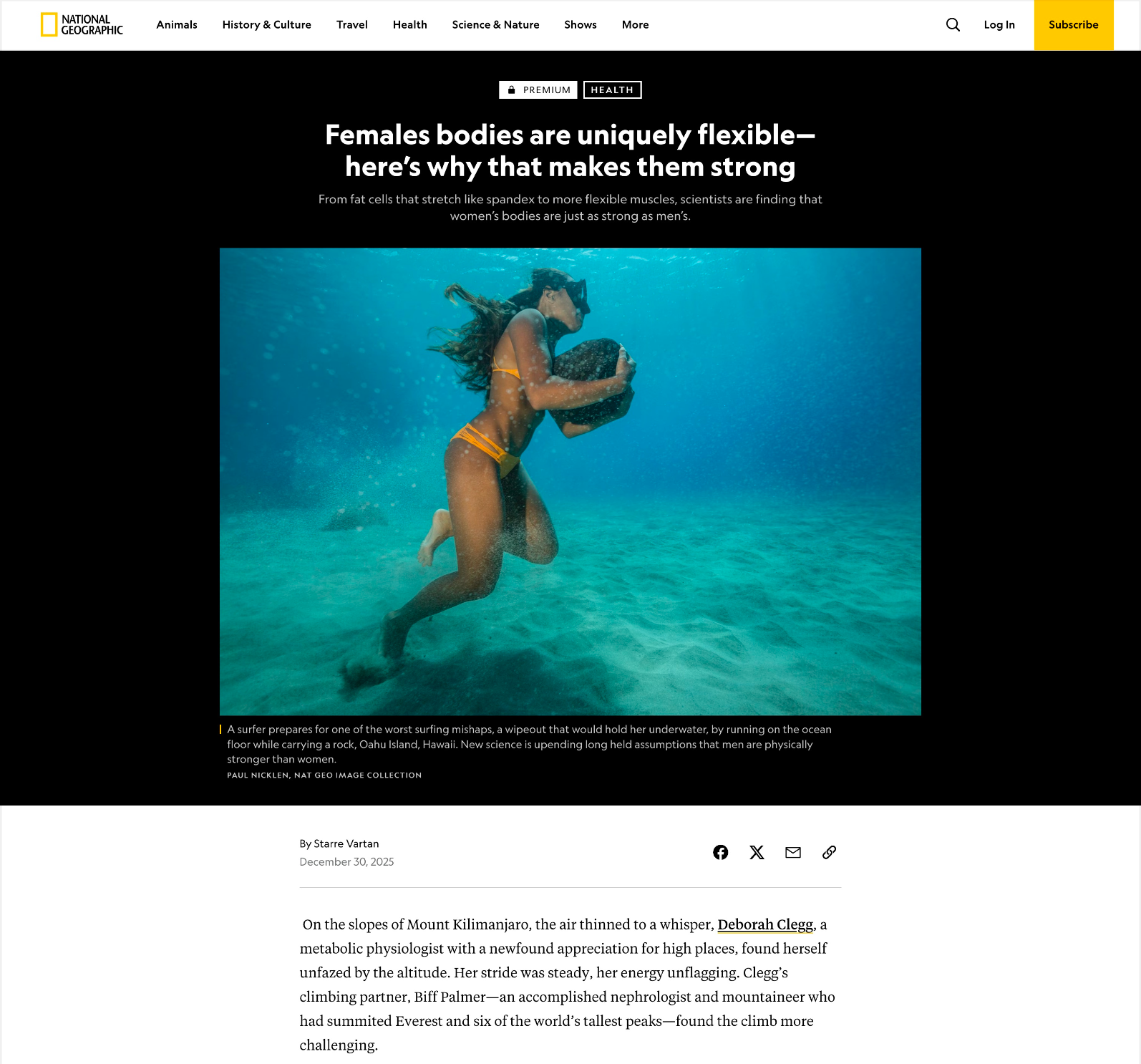

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

I loved writing this piece for National Geographic, which brings together three areas of flexibility (which I argue is an unsung strength) in the female body: bendiness, metabolic, and life-span flexibilities.

We all know that generally female bodies are more stretchy, and I detail a bit about why that is, but my favorite section might be on metabolic flexibility, which is a true superpower, preventing illness and disease even as female bodies carry more fat (which we can then use to power endurance work!).

Lastly, the overlooked flexibility — the incredible changes the female body can go through in a lifetime, from menarche to menopause, a monthly cycle of creating a heroine egg for possible fertilization AND a uterus lining growing and shedding and healing the uterus, and of course the incredible change the female body goes through during pregnancy and postpartum, as well as breast feeding! Male bodies just don’t do any of these things, remaining much more static over time and it’s something we don’t generally acknowledge — the complexity and demand on the body that those changes demand.

And WOW do I LOVE the image my editor chose to accompany the story, by famed photographer Paul Nicklen (worth a follow over on Insta!).

Here’s the lede to the story:

On the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro, the air thinned to a whisper. Deborah Clegg, a metabolic physiologist with a newfound appreciation for high places, found herself unfazed by the altitude. Her stride was steady, her energy unflagging. Clegg’s climbing partner, Biff Palmer—an accomplished nephrologist and mountaineer who had summited Everest and six of the world’s tallest peaks—found bagging Kilimanjaro more challenging.

Following the Kilamanjaro climb in 2013, they continued scaling heights together, and they noticed a pattern. Mountain after mountain, Clegg consistently outperformed Palmer—not through bravado or better conditioning, they observed, but something deeper. Another factor was at play. Their conversations turned from competition to curiosity: why did her body seem so well adapted to the low-oxygen air and long exertion?Back in the lab, they set out to answer that question.

That's all for this round! Thanks for joining me here every month!

In Solidarity,

Starre